“Come on, let’s go have some coffee and leave the kennel to Lassie.” (McCartney, 1964).

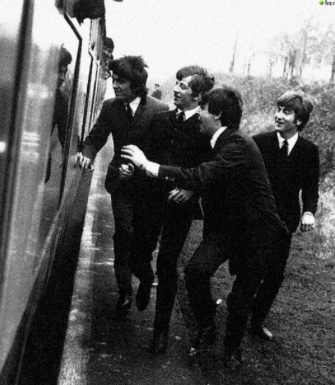

In an iconic scene in the iconic move A Hard Day’s Night, the boundless youthful exuberance of The Beatles runs headlong into the wall of conformity, as epitomized by a stodgy gentlemen passenger on a train. When the lads open the window, the elderly gent shuts it, despite their protests. When the famous Ringo turns on his transistor radio (was that a Beatles song playing?) the ill-tempered man unceremoniously turns it off, condescendingly explaining that his rights as a regular rider (twice a week!) override the rights of the Fab Four. Undeterred, the Lads from Liverpool leave their berth on the train and, in a bit of movie-making magic, appear running beside the train, cheerfully shouting, “Hey mister can we have our ball back?”

I rewatched A Hard Day’s Night last week while I was sick with the flu (an occupational hazard for a teacher) and I was struck by this scene for three reasons: 1) It is a celebration of the resilience of youth, 2) It artfully expresses generational conflict and bias, and, 3) It underscores the importance of play. Allow me elaborate on these three feverish perspectives:

Youthful Resilience

Our most precious natural resource are the hearts and minds of students sitting in our classrooms today. They are filled with all sorts of hopes, anxieties, and aspirations. They are also far more energetic than most of their teachers and have the remarkable ability to apply that youthful energy to learn compensatory strategies with near instantaneity. By that, I mean that young people learn very quickly, and cheerfully, to simply shift directions when things aren’t working out the way they want. Spend some time watching students inventing and playing games in the schoolyard (as Jean Piaget did) and you’ll see what I mean. When the going gets tough, kids get going with a remarkable resilience that is born of youth. That is an force of nature that whole learning systems need to recognize, tap into, and direct towards greater social, emotional, and academic outcomes. What we need to start doing is asking students to think more closely about the strategies they use when their learning gets challenging to them. How do they know what to do when they don’t know what to do? Ask them. They’ll tell you, and more importantly, they’ll reinforce for themselves certain strategies that they most likely apply unconsciously.

The Bias of Ageism

Early in my teaching career I met and fell under the spell of the great Herb Kohl. I had just finished reading his classic work I Won’t Learn From You: And Other Thoughts on Creative Maladjustment when I ran into Herb in 1996 at an iEARN conference at the University of Tennessee in Chattanooga. Herb explained that there exists an unconscious form of bias that informs educational policy and practice called ageism. Ageism is the belief that young students are simply unable to learn creatively and so their learning experiences must be forcibly directed and managed by adults. In its extreme, this bias is made manifest by a form of lock-step standardization and mechanistic adherence to a narrow set of learning pathways and outcomes. This brings to mind high-stakes standardized testing and prescriptive teaching, both of which are unfortunate residues from a group of stodgy gentleman who, at the turn of the 20th Century, decided that their rights as education policy influencers overrode the rights of teachers and learners.

In 1892, a group of college presidents, including the Presidents of Harvard, Vassar, and the University of Michigan, established themselves as the Committee of 10. The Committee of 10 saw the explosive growth in American High Schools across the nation with some alarm and so, much like the grumpy train rider in A Hard Day’s Night, decided to intervene by directing the curriculum according to their experiences as privileged members of American society. They standardized the American schooling experience that was, in no small way, based on an evidence-free, debunked learning notion called “Mental Discipline.” The problem is that Mental Discipline is a flawed concept which recognizes the brain as a “muscle” (it’s not; it’s a brain) that must be trained through regular drill and practice. More than twice a week. An insidious implication of this problem is that the Committee’s flawed vision for American schooling has resulted in the dominant “Tell and Practice” model of instruction in which teachers tell students what knowledge is and what knowledge is important to memorize, with students going about the odious task of memorizing and regurgitating that knowledge on low-value/high-stakes examinations. The successful students don’t forget what they’ve memorized until after the test. Sadly, our current system of education still privileges surface learning through rote drill and practice learning experiences, much to the detriment of deeper learning, knowledge transfer, creativity, and play.

The Importance of Play

We can do better. We can reclaim our students’ youthful exuberance and innovative love of creative learning by recalibrating our concept of learning in the Digital Age. Let’s establish policy that allows our students to leverage modern learning tools to move away from memorizing old knowledge and move towards taking a more active role in planning for their learning, creatively and playfully expressing their knowledge gain, and actively evaluating and assessing their learning. The bankrupt concept of Mental Discipline needs to be replaced with the highly research-based concept of contributive learning in which students mindfully and masterfully address current learning problems, and build the capacity to address future learning problems. The preponderance of evidence strongly indicates that when implemented, these ideas result in a profound acceleration of student learning and achievement. Finally, let’s put play back where it belongs in the learning sequence–both in the classroom for our students, and in the halls of professional learning for our teachers and educational leaders.

Let’s say it all together now: “Hey mister, can we have our ball back?!”

AUTHOR

Dr. Sonny Magana is an award-winning teacher, pioneering educational technology researcher, and best-selling author. A highly sought-after speaker and consultant, Dr. Magana’s latest book, Disruptive Classroom Technologies: A Framework for Innovation in Education, introduced the T3 Framework for Innovation which has been hailed as: “A visionary work; truly insightful and inspirational!” (Marzano, 2017); “A brilliant breakthrough in our understanding and use of technology for learning” (Fullan, 2017); and, “A major step forward; Magana’s T3 Framework offers a credible, powerful, and exciting challenge; let’s do it!” (Hattie, 2018). Dr. Magana’s research findings underpinning the T3 Framework were recently inducted into Oxford University’s inaugural Online Research Encyclopedia for Education.

A tireless advocate for transcending the status quo, Dr. Magana founded and served as Principal of Washington State’s first CyberSchool in 1996, a groundbreaking blended learning program that continues to meet the needs of at-risk students in Washington. He is a recipient of the prestigious Milken Family Foundation National Educator Award and the Governor’s Commendation for Educational Excellence. An avid musician, yoga practitioner, climber, and bee keeper, Sonny was awarded the Milken Family Foundation Educator Award and the Washington Governor’s Commendation for Educational Excellence. He holds a bachelor of science degree from Stockton University, a master of education degree from City University, and a doctorate in educational leadership from Seattle University. He has successfully climbed the highest peaks in his home state of Washington.